A Lifestyle Disease: Chronic Organisational Knowledgeitis

About three years ago I had a persistent sore throat. Nothing agonizing, just persistent. I went to my doctor and he prescribed a course of antibiotics, to no avail. So he sent me to a specialist, who shoved a camera in a tube down my throat and poked around.

About three years ago I had a persistent sore throat. Nothing agonizing, just persistent. I went to my doctor and he prescribed a course of antibiotics, to no avail. So he sent me to a specialist, who shoved a camera in a tube down my throat and poked around.

Afterwards, showing me the video (aesthetically speaking a worse experience than having the camera take it), he carefully pointed out a neat, four-node ulcer sitting just above the larynx.

Then he sat back and looked at me in a headmasterly sort of way. “You have a stressful job? What about your eating habits? Alcohol? Coffee? Spicy food?”

Okaaaayy, I thought, there’s going to be a point to this. And there was. My ulcer was a symptom of an underlying condition called … wait for it … oesophegal laryngeal reflux. It’s a “new” condition – as in newly discovered, but not so new that he didn’t have a leaflet for it. It’s a “lifestyle” illness associated with poor eating habits (what you eat and drink, irregular eating times, eating too close to bedtime) and stressful lifestyle.

When you have this condition, your stomach become overactive in the acid production department. During the day, all that extra acid swilling around just gives you the occasional heartburn.

But at night, when you are horizontal and prone, sleeping off your stressful day, your half digested food and a couple of glasses of wine, your insidious stomach loosens the valve leading back up into your oesophagus, and releases a warm flow of stomach acid along the passage to gently bathe the back of your throat. All completely painless and unnoticed. In the morning, you return to the vertical, and the acid goes back where it belongs.

Eventually, obviously, the surface of the skin starts to break down and ulcers form. If untreated, throat cancer is a higher risk.

I can treat you for the hyper-acidity said the specialist (and he did, with the most expensive antacid tablets I have ever seen – $200 per box of 10), but I can’t cure the condition. Only you can. You have to change the way you eat and sleep – and ideally your stress levels as well. This is why it’s called a lifestyle illness. Hello, I said, I’m running my own startup business, let’s forget stress-reduction and focus on eating and sleeping.

So for three months I had to stay away from most of the joys of life: coffee, alcohol, chocolate, spicy food, fried food, acidic fruit; fruit juices; I had to make sure I ate several hours before I slept; I tried to bolt my food less compulsively and irregularly as if I had no more than the odd couple of minutes in a day for this unproductive task; and I had to sleep propped up on pillows so that my nefarious stomach couldn’t sneak acid up on my throat so easily.

The ulcer disappeared, to the self-satisfaction of my specialist, but even now, more than one cup of coffee and three wine dinners in a week, and my throat starts acting up. And I still sleep propped up on pillows.

There is a point to this story. If the organizational condition that knowledge management treats were to be a medical condition (let’s call it chronic organisational knowledgeitis), it, too, would be a lifestyle disease. Yes, there are “pills” and procedures, in the guise of technology platforms, methodologies and frameworks. But all these can do is palliate surface symptoms, and they don’t always do that – as in my initial course of antibiotics.

Knowledgeitis is a disease of bad organisational habits and misaligned behaviours. It can only be cured through lifestyle changes, deep into the organisation’s structure.

This is why you can’t hire a consultant to come and examine you and prescribe a simple course of treatment and go away again, and expect that all will be well. This is why, you have to engage every level of management from the top down, hunt down and undermine each critical bad habit that contributes to the condition, and insert new, constructive habits – well no, you can’t insert habits, you have to grow them. Many of your attempts will fail.

It’s all slow work that requires patience, consistency and clear sense of purpose. And it’s difficult because until the ulcers appear (perhaps in the form of infoluenza), most people in the organization don’t see there’s a problem at all.

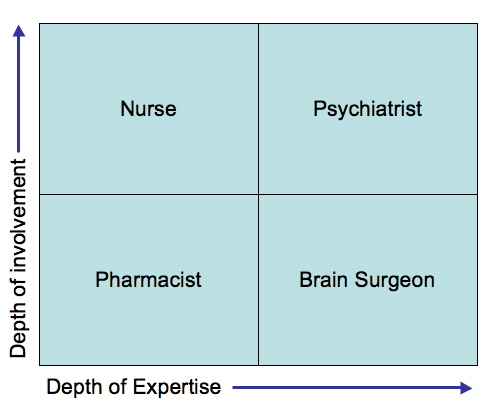

I have been playing for several months now with a lovely framework produced by David Maister to describe how the different kinds of professional services work. Here’s my slightly modified version:

In the “Pharmacist” mode, the condition is simple and well known, and treatment simply means prescribing a pill. Pills are produced in large quantities, so the treatment is relatively cheap, and the engagement is short.

Next to the Pharmacist, we have “Brain Surgeon” consultancy modes. Here the problem is difficult, but the organization doesn’t want, or need, to know the detail of what the condition is. They just want an expert to come in, find the problem and cut it out, collect their cheque and go away again. Their skill and expertise is acknowledged, so although the engagement is brief, they can command high payments.

The upper half of the diagram is a different story, and it’s here that the lifestyle diseases like knowledgeitis get treated. In “Nursing” mode, the engagement is longer, but there are well proven, templated methodologies to use, so you don’t need a lot of support from extremely skilled specialists. Your consultants nurse and coach you through your recovery.

In “Psychiatrist” mode, your problems are more complex and tricky to resolve, and typically this means that you need the support of a specialist for extended periods, to help you identify your underlying problems for yourself, and facilitate you through a recovery.

I like this diagram a lot. It explains really well the role that consultants should play in knowledge management. It explains why pill popping (buying a KM system without any other intervention) and hit-and-run consulting (brain surgery for a digestive disease) just don’t work.

It also explains why it’s hard to make a lot of money in KM consulting, because organizations don’t know – or want to know – about lifestyle illnesses where they have to take some responsibility for their own recovery. Nor do they think that knowledgeitis is an especially important disease, enough to warrant an expensive brain surgeon. Many organisatiins are still fixated on the “prescribe me a pill doctor and don’t take up too much of my time” model of illness, and the money and management effort they are prepared to invest in KM reflects this,

In relation to my throat story and lifestyle illnesses, Maister’s diagram has one drawback – which is that it focuses on the consultant’s role. This is fine for consultants, but we need a better way of communicating to our clients how important their own efforts are in addressing this dread disease: chronic organizational knowledgeitis.

5 Comments so far

- clive flashman

I agree with your comments that too often the cause of the ‘knowledge’ problems at an organisation are self-inflicted and that owning up to having a problem is the hardest part.

Having said that, I wonder if a model (and I understand that models are mainly geared to a snapshot of a situation rather than a period of time) could capture ‘lifestyle’ changes.

Take dieting for example (to continue the health analogy). I am overweight, thereford I need to diet. It is a simple equatin of too many calories in, too little exercise out. There are factors that impinge on this equation such as genetic predetermination, metabolism, culture, etc.

I could go on a crash diet - say cabbage soup. Would this benefit me, maybe in the short term (with some nasty side effects), but it would soon los its impact as I yo-yo’d back to my original weight (or higher).

Since eating a sensible diet, and exercising in mderation is a lifestyle decision - let’s look at when it actually works for people:

1) When they’ve had a ‘wake-up call’ such as a heart attack or stroke

2) When someone close to them has a ‘wake up call’

3) When someone they respect warns them of what will happen if they don’t change

4) When someone makes it as easy as possible for them to adapt their lifestyle (healthy meals provided, exercise coach on call)

5) When it is a competitive situation (but this tends to be short-term).In the business world - what is the wake up call?

If we were looking for warning signs, what would they be?

I really like the healthcare analogy (given that I currently work in the NHS) and it has got me thinking about the whole issue of KM as a matter of organisational lifestyle change!

Just remember that you did ask me to debate this one Patrick

Response here

- Nimmy

Patrick,

Very interesting post!

I love the analogy...! Maybe what organizations pursuing KM need is a good mix (team) of all the 4 profiles....the nurses and the psychiatrists/psychologists preferably from within the organization and working hand-in-hand with the pharmacists and brain surgeons who could be (external) consultants....

Just my initial thoughts...your analogy motivates me to explore things a bit more on the same lines…

Nirmala

- Persiangirl

Thanks sooo much! This blog has just helped me, a 14 year old girl in High School in South Africa, with my project!

Our class was to choose a lifestyle disease and do an oral on it, I wanted mine to be unique and different, not like most of the other pupils who are doing obesity and Alzheimers disease!!!Thanks soo much, again, please reply to this comment at

PS if you know any persian breeders or yorkshire terrier breeders please tell me!!! It doesn’t matter if they are over seas!!!!!

Persiangirl

Page 1 of 1 pages

Comment Guidelines: Basic XHTML is allowed (<strong>, <em>, <a>) Line breaks and paragraphs are automatically generated. URLs are automatically converted into links.

Glad to see that you are on the mend Patrick. I would dispute one aspect of your diagram though. I would prefer the term pyschologist to psychiatrist. Psychologists tend to look at the underlying emotional issues whereas psychiatrists often tend to go down the medication path and could be clsoer to brain surgeons(each useful in their own context but I think that your description is closer to psychology).

Posted on June 29, 2007 at 10:25 AM | Comment permalink